I really enjoyed the job I had in 2015. I was a principal engineer at a health tech company, with a polyglot team comprised of Ruby and Clojure developers ranging from very early career to very seasoned. I was learning a lot and doing really interesting work. I felt like I had finally found a company that I could stick with for a few years or so.

Then I got a strange message on Twitter. Someone at GitHub wanted to talk to me. I thought I knew what it was about: a year before, I had been talking to a diversity consultant (who was contracting there at the time) about working with GitHub on diversity and inclusivity and exploring their interest in adopting the Contributor Covenant across all of their open source projects.

But that's not what they wanted this time. They wanted to offer me a job. They had just created a team called Community & Safety, charged with making GitHub more safe for marginalized people and creating features for project owners to better manage their communities.

At first I had my doubts. I was well aware of GitHub's very problematic past, from its promotion of meritocracy in place of a management system to the horrible treatment and abuse of its female employees and other people from diverse backgrounds. I myself had experienced harassment on GitHub. As an example, a couple of years ago someone created a dozen repositories with racist names and added me to the repos, so my GitHub profile had racial slurs on it until their support team got around to shutting them down a few days after I reported the incident. I didn't get the sense that the company really cared about harassment.

"These values aren’t just for GitHub users or externally facing decisions. These are beliefs we bring into every interaction, whether it’s a co-worker, partner, user, or competitor. These values guide our behavior and decisions."

-- From "Values" by GitHub CEO Chris Wanstrath

My contact at GitHub insisted that the company was transforming itself. She pointed to a Business Insider article that described the culture changes that they were going through, and touted the hiring of Nicole Sanchez to an executive position leading a new Social Impact team. I was encouraged to talk to some other prominent activists that had recently been hired. Slowly, I opened my mind to the possibility. Given my work in trying to make open source more inclusive and welcoming, what could give me more influence in creating better communities than working at the very center of the open source universe?

With these thoughts in mind, I agreed to interview with the team. The code challenge was comparable to other places where I’d interviewed, as was the pairing exercise. I was impressed by the social justice tone of some of the questions that I was asked in the non-technical interviews, and by the fact that the majority of people that I met with were women. A week later, I had a very generous offer in hand, which I happily accepted. My team was 5 women and one man: two of us trans, three women of color. We had our own backlog separate from the rest of the engineering group, our own product manager, and strong UX and QC resources. I felt that my new job was off to a promising start.

"Collaboration. We believe the best work is done together. Work with other teams. We are all first and foremost GitHubbers. Deliberately seek to collaborate with a diverse set of people. Provide context on decisions to collaborate with the future."

-- From "Values" by Chris Wanstrath

However, it soon became apparent that this promising start would not last for long. For my first few pull requests, I was getting feedback from literally dozens of engineers (all of whom were male) on other teams, nitpicking the code I had written. One PR actually had over 200 comments from 24 different individuals. It got to the point where the VP of engineering had to intervene to get people to back off. I thought that maybe because I was a well-known Rubyist, other engineers were particularly interested in seeing the kind of code I was writing. So I asked Aaron Patterson, another famous Rubyist who had started at GitHub at the same time as I did, if he was experiencing a lot of scrutiny too. He said he was not.

Shortly after this happened to me, the code review feature was prioritized. This functionality was rolled out internally pretty quickly. From that point on I didn't get dogpiled anymore, since I could request reviews from specific engineers familiar with the area of the codebase that I was working in and avoid the kind of drive-by code reviews that plagued my initial PRs.

A couple of months later, I finished up a feature that I was very excited about: repository invitations. With repository invitations, no one could add someone else to a repository without their consent. Being invited to contribute to a repository resulted in an email notification, from which the recipient could accept or decline to join and even report and block the inviter.

Feature releases such as these are frequently promoted on the GitHub blog, and the product manager on my team encouraged me to write a post announcing what I had shipped. Since it was so important to me personally, I wrote an impassioned piece talking about how this feature closed a security gap that had directly affected and provided an abuse vector against me. The post also served as an announcement to the world of the new team and the kinds of problems that we were charged with solving.

The post was submitted for editorial review. It was decided that the tone of what I had written was too personal and didn't reflect the voice of the company. The reviewer insisted that any mention of the abuse vector that this feature was closing be removed. In the midst of my discussions with the editorial team, trying to reach a compromise, a (male) engineer from another team completely rewrote the blog post and published it without talking to me.

Through my previous jobs I had grown accustomed to pair programming. I have found that in addition to the positive impact that pairing has in terms of code quality and bug reduction, the experience of working directly with another developer (whether more junior or more senior) provides a wealth of learning and teaching opportunities. As a seasoned developer I have certain quirks, opinions, and common patterns that I fall back on. Having to explain to another person why I am approaching a problem in a particular way is really good for helping me break bad habits and challenge my assumptions, or for providing validation for good problem solving skills. But pair programming simply didn't happen at GitHub. I would occasionally get another engineer to share a screen to walk me through a particularly hairy subsystem, but actual pairing was extremely rare and I missed it.

In addition to my development work, I had started weekly mentoring sessions with one of my teammates (a recent boot camp graduate) on Ruby and Rails fundamentals that she had not been exposed to in her program. When I talked to my manager about how she was progressing, I was told to stop the formal mentoring and allow this person to "learn at her own pace, without any pressure from you." I was mystified: mentoring is an essential part of being a senior engineer, and this teammate seemed to be benefiting from it. But I did what my manager told me to do.

Collaboration in general was not easy. Remote-friendly companies generally rely on video chat to discuss development strategies and architecture decisions, to establish and review priorities, or even just generally check in on the team. But GitHub was different. We had our daily standups on video chat but that was the extent of real-time communication. Discussions were directed to comments on issues and pull requests. Even if you talked to someone on Slack, you were expected to provide a link to the conversation in a comment. Asynchronous communication is sometimes necessary on a distributed team, but never in my career have I seen it taken to the level that GitHub has. Asynchronous communication is definitely not my strongest area. When I see a text box on screen, I tend to be very terse and direct instead of typing out a wall of text.

"Positive Impact. We believe in making the world a better place through our work. Make GitHub a role model for the industry. Be a great neighbor and member of the community. Build inclusive culture."

-- From "Values" by Chris Wanstrath

That summer I was invited to attend an offsite retreat for the open source team. We met to discuss and propose objectives and goals for the team for the coming year. It felt really good to be included in these discussions, and there was definitely a spirit of collaboration at work. One of the things that I suggested at that retreat was the implementation of a survey of GitHub users. In contrast with the (problematic) Stack Overflow developer survey, we would ask questions that would shed light on participation in open source by otherwise uncounted marginalized people. We would be the first to provide data on participation by people of color, people on the LGBTQ spectrum, transgender men and women, non-binary developers, and more. The idea met with unanimous approval.

One day a notification came to me that a repo for the open source developer survey had been created and that the survey questions were in progress. My director followed up with me to make sure that I was aware of the survey and asked me to review the questions. I worked my way through, and stopped short at one particular question: "What is your gender?" The multiple-choice options were "Male", "Female", and "Transgender". I was very disappointed at this 101 mistake, and sadly opened an issue referencing the question. The body of my issue read:

"'Transgender' is not a gender. Transgender people may be male, female, gender queer, non-binary... If you want to know if a survey respondent is transgender, you need to explicitly ask that question."

I left some other minor feedback on other questions, and resumed my regular work. The next day I got an urgent request for a call with my manager. She told me that the data scientist who had written the survey questions was very upset and had gone to her manager to complain about me. I asked my manager what had happened to upset her and was told that it was the feedback I provided on the gender question. I read back to her the body of the issue that I had opened and asked what I should have done differently. She responded that she didn't know, that my wording seemed direct but non-confrontational, but that I was forbidden to interact any further with the author of the survey.

This was the first instance of what came to be referred to as my "non-empathetic communication style".

In another case, in a discussion about giving project owners the power to edit other people's comments in issues and pull requests, I mentioned my experience with the opalgate incident and pointed out how if the openly hostile maintainers of that project had the ability to edit my comments, the situation would have been even worse than it already was. I pleaded that this feature be reconsidered from the perspective of potential abuse. My manager accused me of shutting down the conversation by making it personal.

In speaking up like this, I felt like I was simply doing my job. I was trying to make a positive impact by speaking up for the minority of users who are regularly targeted for abuse. I wasn't just trying to represent the values of the Community & Safety team, I was trying the represent the values of marginalized communities.

I tried my best to make a positive impact. I kept the needs and best interests of the most vulnerable people on our platform at the front of my mind at all times, and prioritized my work according to what would make the biggest difference to this population of users. I was responsible for the open source developer survey, which was the first of its kind to measure the participation of marginalized people in tech. I recruited for the company, reaching out through my network and assuring people that while GitHub was still a work in progress, things were getting better there.

"Shipping: We believe in creating things for the people using them. Ship early and often. Embrace change. Constantly strive to improve through iteration."

-- From "Values" by Chris Wanstrath

Throughout all this my work with my team progressed. I was working quickly through the backlog of features. We also had what we considered technical debt, in the form of existing GitHub features and processes that inadvertently presented open harassment vectors. Since abuse on the platform was not something that had been seriously considered before, there were lots of areas where things could happen to a user without their consent and leave them vulnerable or worse.

I shipped a lot of code. As I recall, in the 14 months that I was there, I closed over 200 pull requests. And as the most senior developer on the team, I took on many of the harder and more complex features and bugs. I was consistently praised for my productivity.

There were certain features that I was passionate about but that I had to defer working on due to other priorities. I did the work that was prioritized and did my best to be patient.

My boss frequently pointed out that I was consistently shipping more code than anyone else on the team. My bug rates were very low, and when bugs did get reported, I fixed them very promptly.

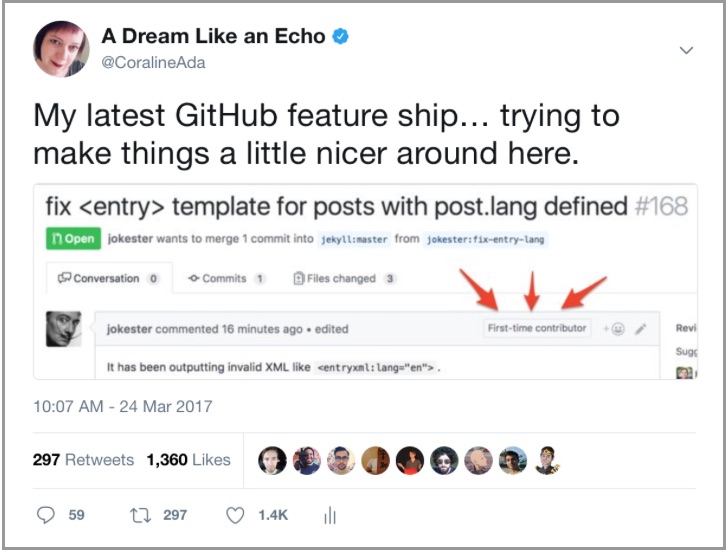

One small feature that I shipped got a lot of attention: the first-time contributor badge. Basically, this was a little badge that a project maintainer would see next to the name of a new contributor to that project. The idea was that the maintainer would feel inclined to be extra polite, friendly, and welcoming to the newcomer, to ensure that their experience was as positive as possible. People loved it.

Finally in January I got the chance to work on the one feature that I wanted GitHub to have most of all: a tool to make adding a code of conduct to a project easy. After an initial proof of concept, I worked closely with the team's UX person to create a very streamlined experience. We had been tracking code of conduct adoptions since the summer of 2016, and seeing growth at a rate of 500 projects per month. I was eager to see this rate increase with the addition of the new tool.

The code of conduct adoption feature was launched in May 2017, and was widely praised. It would be my last feature for GitHub.

"Empathy: We believe in putting people first. Step back and try to understand others’ point of view. Admit your mistakes. Allow others to make mistakes. Help others grow and succeed.”

-- From "Values" by Chris Wanstrath

Starting in December, in my weekly one-on-one meetings with my manager, we would review all of my written communication (issues, pull requests, code reviews, and Slack messages) to talk about how I could improve. It felt ridiculous but I went along with it, and did my best to address my manager's feedback and concerns. I even got a book on constructive communication and effective collaboration and reported in regularly on what I was learning from the reading. My manager seemed satisfied with my progress.

In April it was time for my annual review. Based on the positive feedback from my one-on-ones and how well I was tracking against the goals set for the next engineering level, I was hopeful of getting a promotion and a raise. But when I joined the video call with my manager, it became clear that something was wrong. She went back to the issue of my lack of empathy in communications and collaboration. I brought up the fact that we had been actively working on improving that over the past several months and that I had been tracking well against the goals we agreed to, but she said that the review period was only through January so that progress didn't count. She went on to say that I was not fulfilling my responsibilities as an engineer because for the first month after a new developer was added to our team, I had not done any code reviews for her. I told my manager that I only participated in code reviews to which I was invited, in large part because of my experience at the beginning with drive-by reviews, and that the new developer hadn't started requesting reviews from me until February. Again, the facts didn't seem to matter.

My overall review was a "Does Not Meet Expectations." I was shocked and upset. A bad review out of the blue was not something that I had experienced before. I thought I had good rapport with my manager, and that if there was a problem that we would have been addressing it at our weekly meetings. In my mind this was a serious management failure, but there was apparently nothing I could do about it.

The same day that I had this review, I got some devastating personal news. I have bipolar depression and was already in a bad place mentally, so I found myself feeling crushed and hopeless. In an attempt to deal with things I ended up taking a dangerously high dose of my anti-anxiety medication. When I reached out to my therapist for help, she recommended that I go to the emergency room. This was the start of an eight day ordeal involving involuntary commitment to a mental health facility. I shared this experience on Twitter and won't rehash it here, but suffice it to say that I was severely traumatized by what happened to me in the hospital.

When I finally got out, I met with my therapist to discuss the trauma I had suffered and to talk about how best to recover. She told me that I needed to go back to my routines as quickly as possible, to resume normal life. So I decided to return to work that Thursday.

Thursday and Friday were not good days. I had a lot of trouble focusing. I was making simple mistakes and in some cases doing the wrong work. Friday afternoon I reached out to my boss to tell her that I was having trouble and that I didn't know what to do. She suggested that I take medical leave, but I told her what my therapist had said about the importance of getting back to normal life. My manager was adamant that if I couldn't work at full capacity that I had no choice but to take medical leave. I asked if we could get together a few times a week when I returned from traveling, to review what I was doing and determine if I was working effectively; if I continued having problems I would take some time off. She agreed.

The following week I had scheduled conferences to attend, so my focus on work was put on hold. The day I got back from my trip my manager had set up a conference call. I was confused to see a person from HR there. My manager told me that I was being put on a performance improvement plan (PIP), and that if I did not show improvement soon then they would be forced to let me go. I asked about what we had previously agreed to, accommodating my mental health issues, and she insisted that the PIP had to move forward immediately. The two main areas that I needed to address were empathetic written communication and a target of reviewing 60% of the team's pull requests.

After the meeting I messaged her and shared the more personal aspects of what I was going through, the trauma that I had experienced in the hospital and its lingering effects on my mental health. I was told that I should have accepted the offer of medical leave, and she said she felt like I was trying to manipulate her by sharing my feelings in the hopes of influencing the PIP. I was dismayed.

A week later we had our first PIP tracking meeting. I had created a shared Google doc with the specific details of the PIP and used the document as a daily journal to record what I was doing in each area. In the meeting my manager wasn't interested in talking about what I had written down, and instead criticized me for actively soliciting invitations to do code reviews during our morning standups and pointing out that I had three tracking issues open that should have been closed. Her overall assessment of my week: "Does Not Meet Expectations".

Another week went by. Feeling the pressure of her scrutiny, I made checklists for interpersonal communications, technical communications, and development workflow to make sure that I didn't miss anything. I meticulously recorded everything that I did or said in the shared doc.

The second PIP tracking meeting arrived. Once again I shared the notes that I had taken, demonstrating my commitment to the goals of the process and showing how I was was addressing them. Once again my manager wasn't interested in what I had written down. She told me that a few days back during our stand-up I had said "I got what I needed from ___ so I am ready to start working on this PR." She said that this was yet another example of non-empathetic communication: what I should have done was to explicitly thank ___ , which I had done the next day in what she described as "an afterthought". Overall assessment for week two: "Does Not Meet Expectations".

I finally realized that the PIP process was a mere formality. I was going to be fired and it didn't matter what I did. I decided to start looking for a new job. The following weekend I got more bad news: my grandmother, with whom I had been very close, had passed away. I bought plane tickets immediately and told my manager that I was taking bereavement leave for a week.

I returned to work the following Monday, in time for the third PIP tracking meeting. Once again I had kept thorough notes, had followed all my checklists, had read and reread every written communication to make sure that my words and tone were above criticism. When the call started, my manager immediately told me that I had not shown any improvement and that I was being let go. I would receive one month's salary in severance. My access to all things GitHub was revoked even as she was talking to me: right away I saw that the shared Google doc greyed itself out and an alert about my account popped up. There was no recourse. I had been fired.

Was politely calling out a data scientist on a problematic and transphobic survey answer a demonstration of lack of empathy? What about sharing my personal experience of harassment in a discussion about a feature that could easily be abused? Would it have made a difference if I had thanked my co-worker in that standup?

GitHub touts its values, but has consistently failed to live up to them. Values that are expressed but that don't change behavior are not really values, they are lies that you tell yourself.

I think back on the lack of options I was given in response to my mental health situation and I see a complete lack of empathy. I reflect on the weekly one-on-ones that I had with my manager prior to my review and the positive feedback I was getting, in contrast to the surprise annual review. I consider the journal entries that I made and all the effort I put in on following the PIP and demonstrating my commitment to improving, only to be judged negatively for the most petty reasons. I think about how I opened up to my manager about my trauma and was accused of trying to manipulate her feelings. I remember coming back from burying my grandmother and being told that I was fired.

GitHub has made some very public commitments to turning its culture around, but I feel now that these statements are just PR. I am increasingly of the opinion that in hiring me and other prominent activists, they were attempting to use our names and reputations to convince the world that they took diversity, inclusivity, and social justice issues seriously. And I feel naive for having fallen for it.

In the past several months GitHub has fired at least three transgender engineers and many more cisgender women. Prominent people who were trying to effect positive change in the company culture have quit. They canceled a conference when they got called out for having an all-male speaker lineup. In a return to its meritocratic roots, the company has decided to move forward with a merit-based stock option program despite criticism from employees who tried to point out its inherent unfairness. And the widely publicized results of the open source survey show that the company's platform is still not appealing to anyone but straight white guys.

So yes, in looking back over my year at GitHub I see that there was, in fact, a real problem with empathy.

But that problem wasn't mine.

Follow up: please see the thread starting with this tweet for some important clarifications.